Saint Paul's Episcopal Church

Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Skinner Organ Company, Opus 712, 1928

One of the best-known instruments in North Carolina is the 1928 Skinner organ in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Winston-Salem. Located in two side-by-side chambers speaking into the elegant chancel of this Ralph Adams Cram building, Opus 712 is owned by a congregation with a strong sense of stewardship for their heritage. They have taken excellent care not only of the instrument, but also of the furnishings and building in which they are placed.

Another factor contributing to the preservation of the instrument’s integrity over the years is the lack of frequent turnover of musicians who have held the post of organist at the church. In sixty-eight years, only two people, Mary Frances Cash and Margaret Müller, have occupied the organ bench at St. Paul’s! Upon Mrs. Müller’s retirement, the present organist, Jack Mitchener, was appointed organist of St. Paul’s Church.

Even for seasoned organ restorers, the opportunity to return an instrument such as Ernest M. Skinner’s Opus 712 to its pristine glory comes along but rarely. At St. Paul’s Church, all of the critical elements were in place; here was an unaltered major instrument by possibly America’s greatest organbuilder, installed in one of Ralph Adams Cram’s finest parish churches. The organ had been carefully maintained and sympathetically played over the years, for a large and vital congregation with a keen sense of stewardship towards the many treasures entrusted to its care. The members of St. Paul’s Church simply wanted to preserve this heirloom so that it might be passed on to those who someday will follow. In the eyes of the organ restorers, this was love at first sight.

To be sure, Dr. Cram and Mr. Skinner had conspired unwittingly to create a formidable task which eventually would have to be addressed. The instrument, almost seven tons of it, had been tightly installed in two adjacent chambers; now, in an exacting and complex sequence, it would have to be removed piecemeal through two beautifully carved organ screens concealing the tone openings into the chancel. The narrow, winding cast-iron stairway to the organ chamber would be of little use in removing most of the instrument. Furthermore, the organ would have to be kept available for regular church services during the time it was being restored. Everything would have to be done while St. Paul’s congregation continued to marry, bury and worship in their church: this giant Chinese puzzle would have to be solved under the watchful and protective eyes of its owners.

Work began in January 1996. Worshippers soon became accustomed to odd-looking pieces of the organ, normally visible only to technicians, occasionally strewn all over the building during the comings and goings of the instrument. Because St. Paul’s is such a busy place, a considerable amount of co-ordination was necessary to keep the project moving ahead without interfering unduly with the regular activities of a vigorous church. The entire process would take eighteen months, and except for a two-month period when the organ’s console was emptied for restoration, Mr. Skinner’s versatile instrument continued to serve the daily needs of St. Paul’s Church.

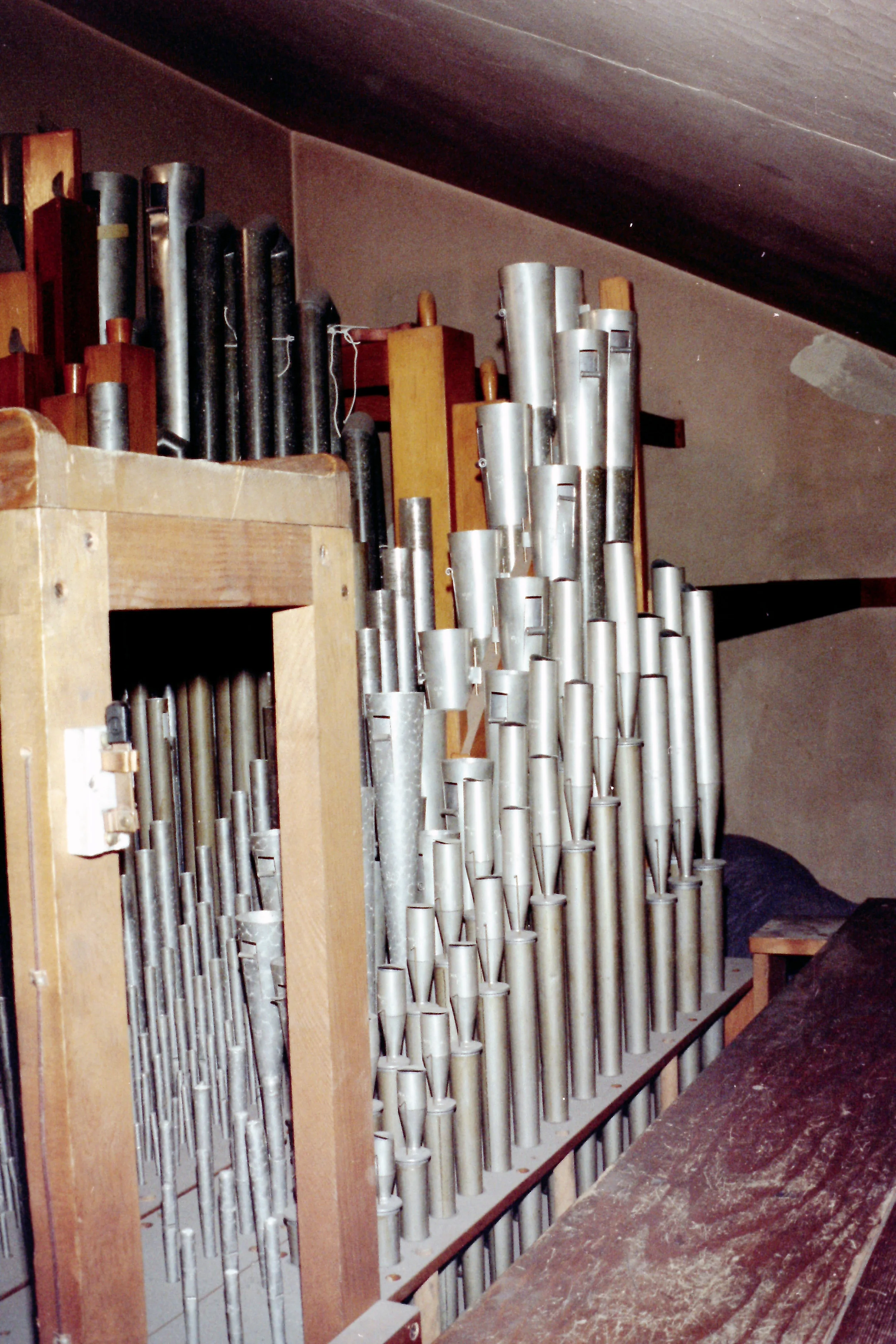

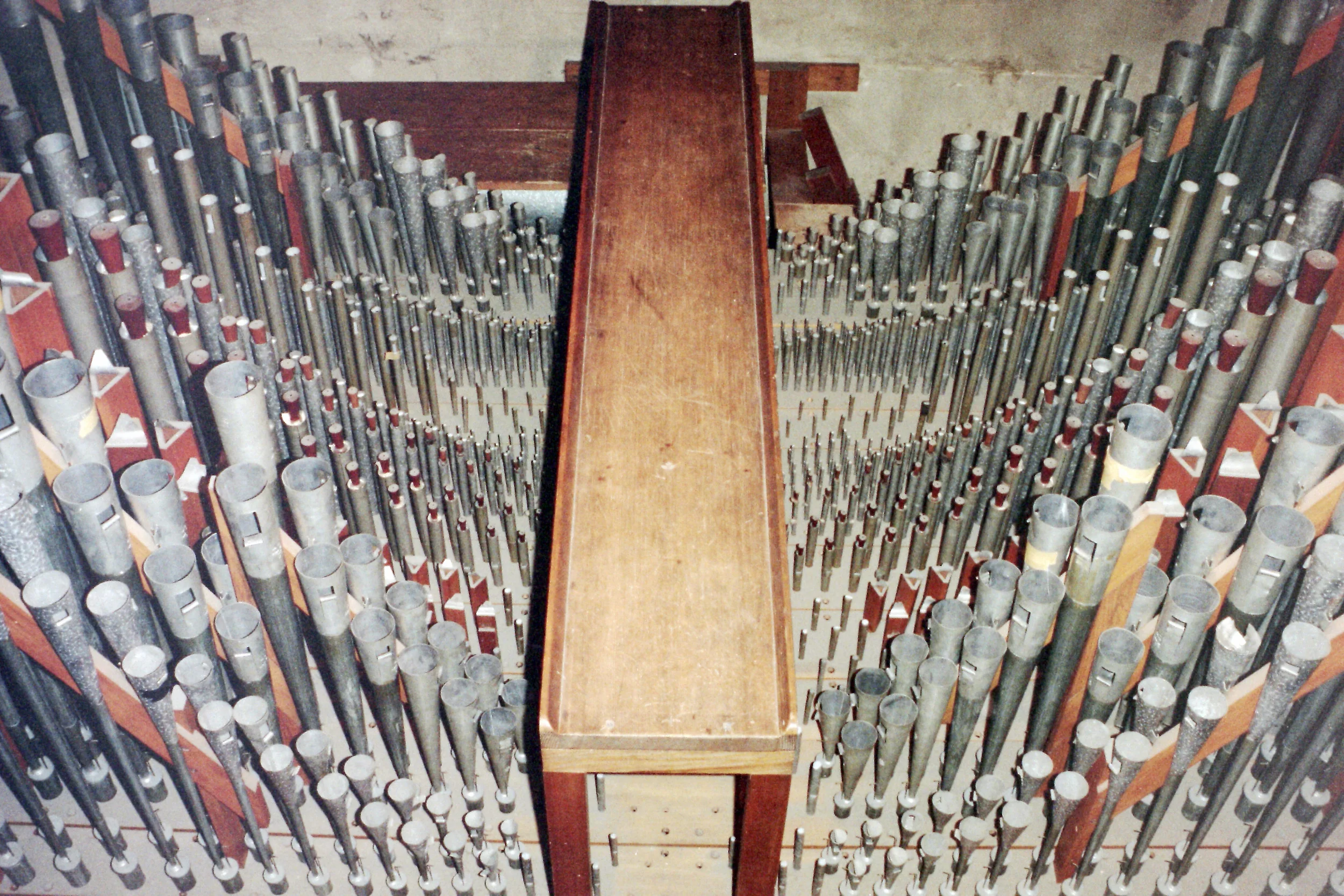

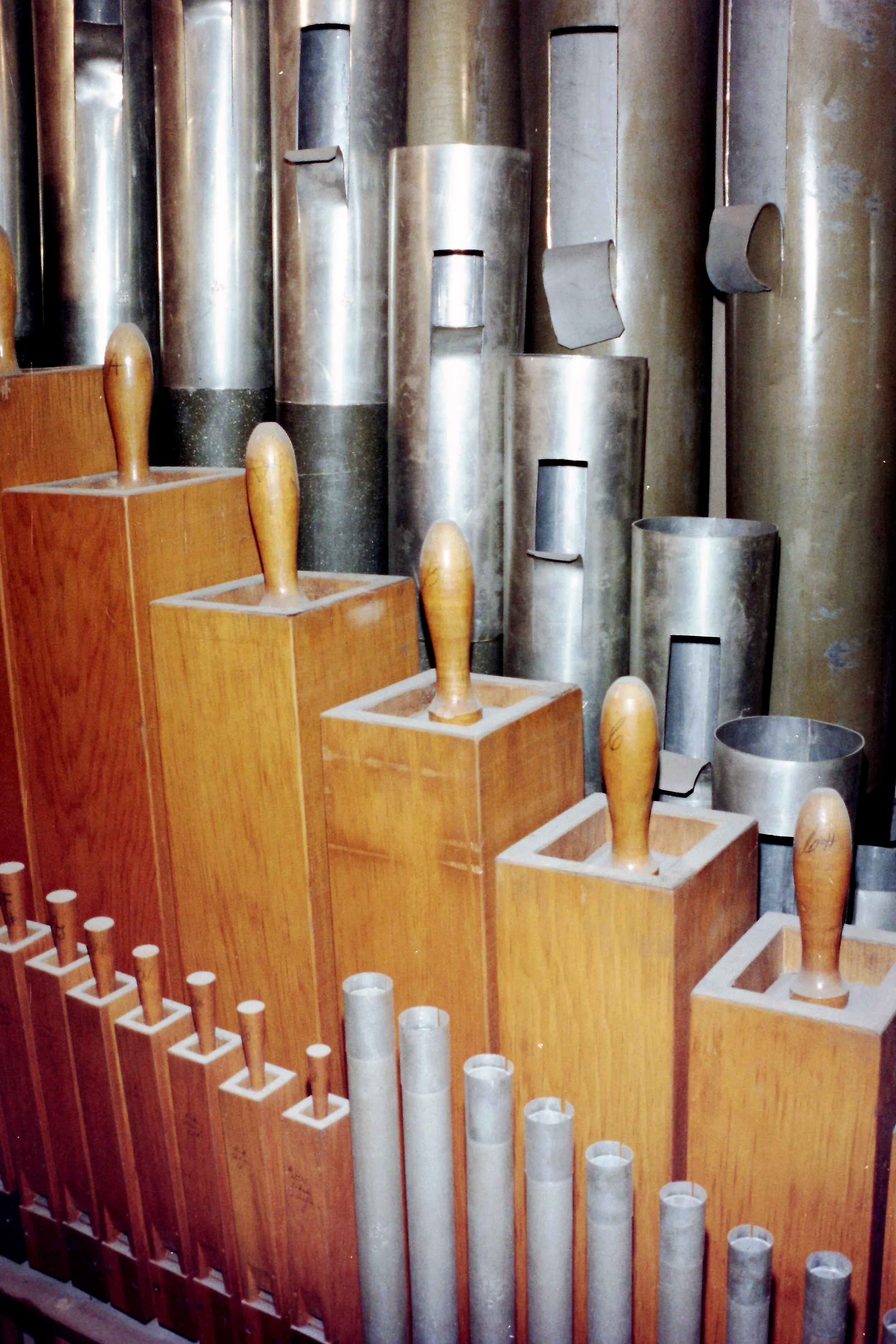

Back in New Haven, in what might be described as a kind of health spa for pipe organs, every part of Opus 712 was cleaned, renewed, polished and pampered back to its original 1928 condition. The beautifully handmade metal pipes were scrubbed spotless, repaired, and fitted with new tuning sleeves; wood pipes were cleaned and their finishes rejuvenated, carefully preserving the old-fashioned handwriting left by the Skinner firm’s voicers many years ago. Of particular interest were the pipes of the 32’ Bombarde stop in the Pedal Organ: customarily these huge floor-shakers were made of thick sugar pine, but at St. Paul’s they appear for the first time made of heavy-gauge zinc, no doubt an experiment which proved successful for it later became the firm’s standard practice.

Another discovery concerned the Trumpet pipes in the Great Organ. Each of these pipes has “764” scratched upon it, which is the opus number for an organ built for the Greenwich, Connecticut, home of Percy Rockefeller, one of John D’s nephews. We can only speculate, but it is likely that Mr. Skinner substituted these Trumpets during the finishing process at St. Paul’s, probably to obtain a different kind of sound than he had initially intended. No one knows where the original Trumpet pipes marked “712” eventually found their home.

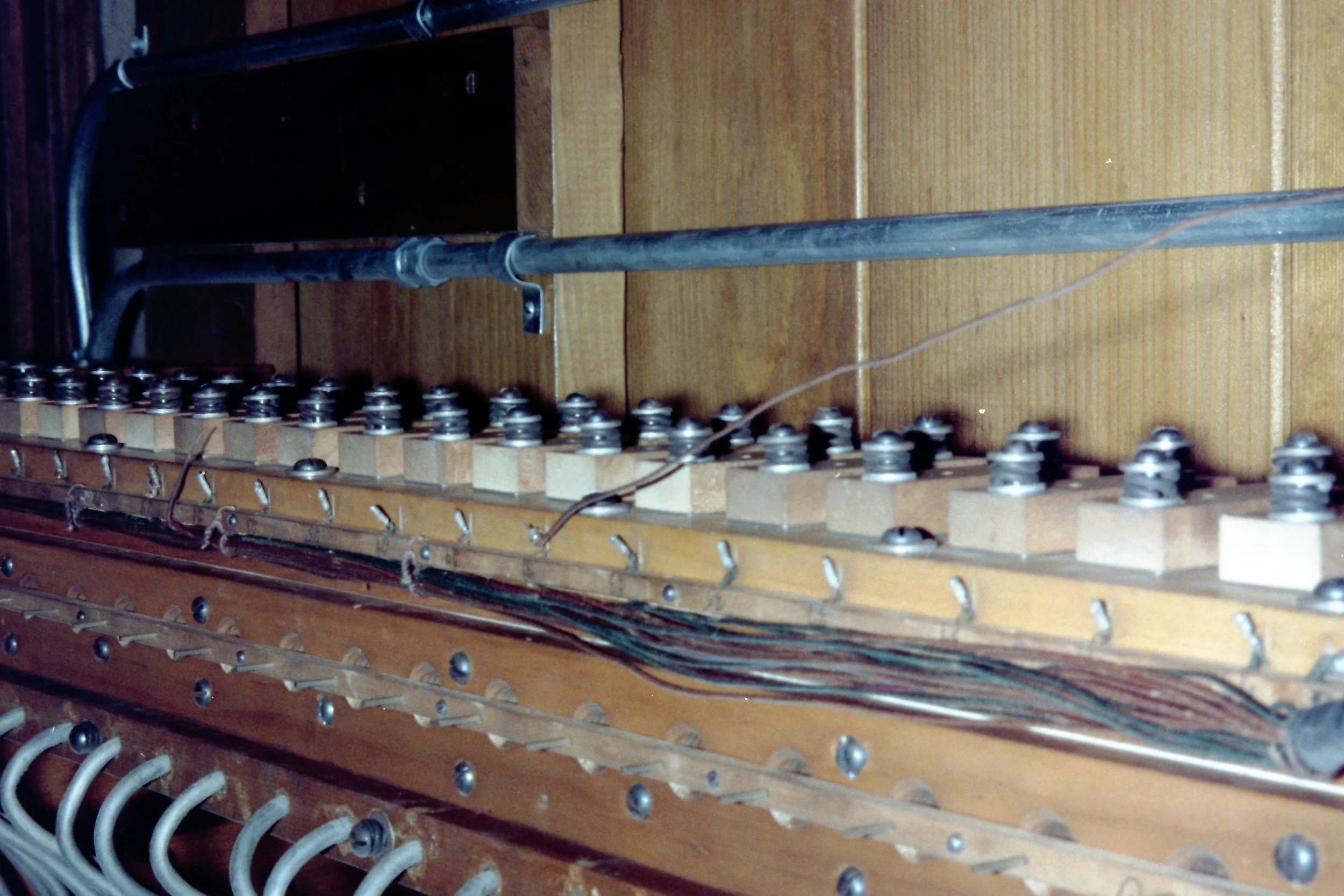

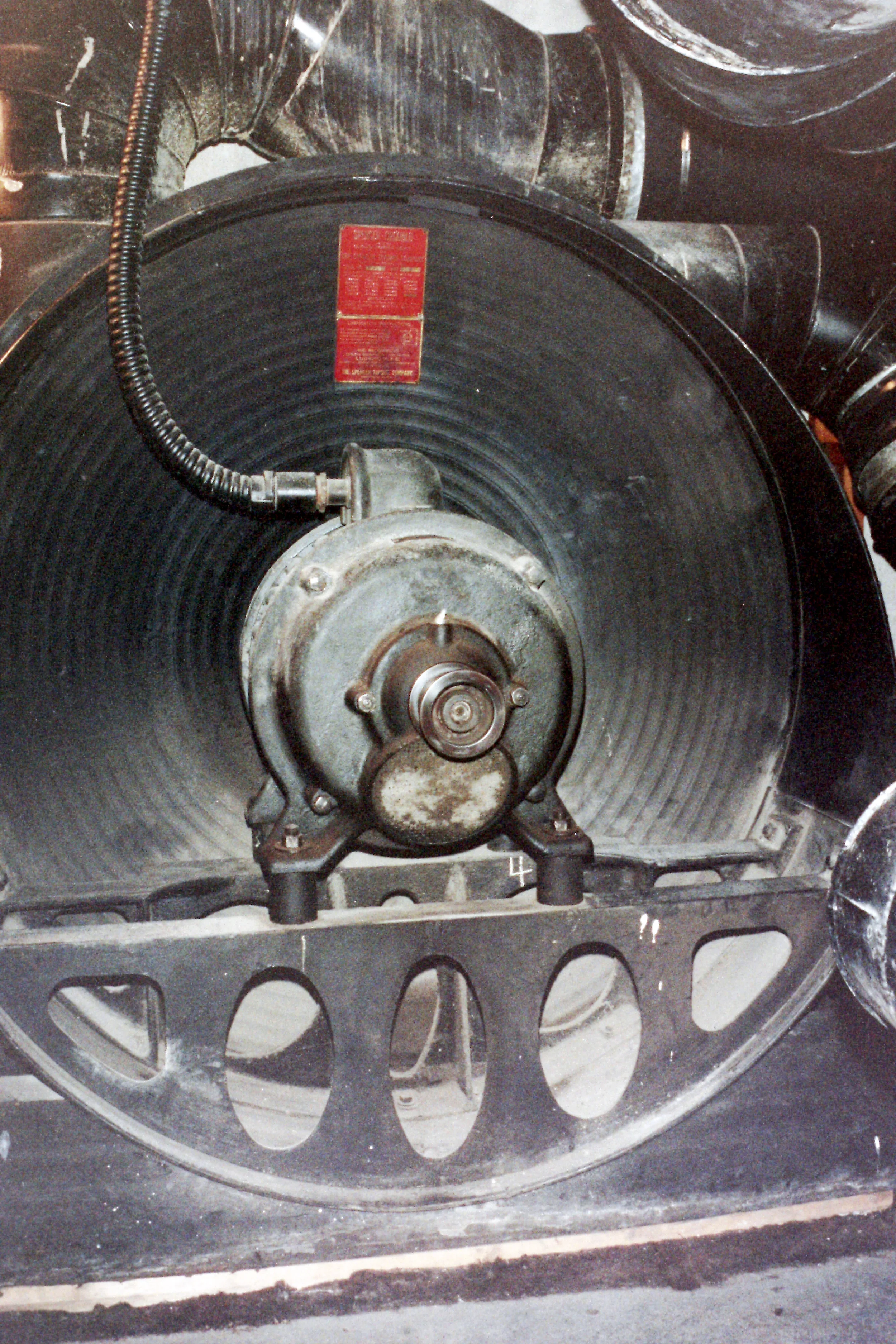

While the 3,473 pipes were being restored, the mechanism of the organ was completely disassembled and renewed. Since the builder’s design had proven so reliable and durable, no attempt was made to improve upon the time-tested technology of the instrument; rather, perished parts were replaced with only the finest quality new materials, painstakingly installed to the builder’s exacting standards. Over 8,700 valves were cleaned and replaced, along with the thousands of leather diaphragms which move them. Metal wind trunking was repaired and regasketed, all woodwork refinished, and the ceilings, walls and floors of the chambers given two coats of paint to promote sound reflection into the church. Lastly the organ console, with its remarkably intricate and refined mechanism (actually an electro-pneumatic computer), was taken to pieces and rebuilt, scrupulously preserving its sophisticated machinery and the unmistakable “feel” of an original Skinner console.

An unusual challenge appeared in dealing with the Harp/Celesta in the Choir division. One of the most delightful (and expensive) stops in the organ, this is a percussion device which produces tones when tuned metal bars are struck by padded hammers, and its considerable bulk is thoroughly impacted in the most inaccessible corner of the chamber. Mr. Skinner doubtlessly assumed that the Harp would be taken out and overhauled along with everything else in the organ at some future time. Unfortunately the mechanism had been hideously damaged many years ago in a misguided attempt to extract the Harp without emptying the entire chamber first. About one-third of its mechanism disappeared, and most of what remained languished in sad disarray. The Harp fell silent for many years and almost everybody forgot about it.

Fortunately the restorers had another Skinner Harp in storage, removed many years ago from Old St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Philadelphia (Skinner Opus 862). Except for the most subtle differences, it was identical to what remained of the St. Paul’s Harp. The Winston-Salem Harp could have been scrapped and the Philadelphia Harp reconditioned and installed in its place, but in the spirit of restoration this was not done. Instead, the Philadelphia Harp was merged with what remained of the Winston-Salem material, in order to preserve as much of Opus 712’s fabric as possible, or “robbing St. Peter's to play St. Paul's” as one wag put it. Even the missing swell-engine (which opens and closes the expression shades in front of the Harp) was replaced with an identical Skinner engine called out of retirement from the dead-storage locker.

Throughout the project it was the intent to carry out a thorough, sensitive and transparent restoration, one which respected the integrity of the organ as well as the genius of the people who built it more than seventy years ago. This was done partly because, to paraphrase architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable, the future will judge us not only by what we create, but also by what we allow to remain. More importantly, however, this was done as a gesture of faith between generations, in order that this extraordinary instrument, which has been carefully preserved and passed down to us, might continue to comfort and inspire others for many years to come.

AFTER RESTORATION