Saint Luke's Episcopal Church

Evanston, Illinois

Skinner Organ Company, Opus 327, 1921

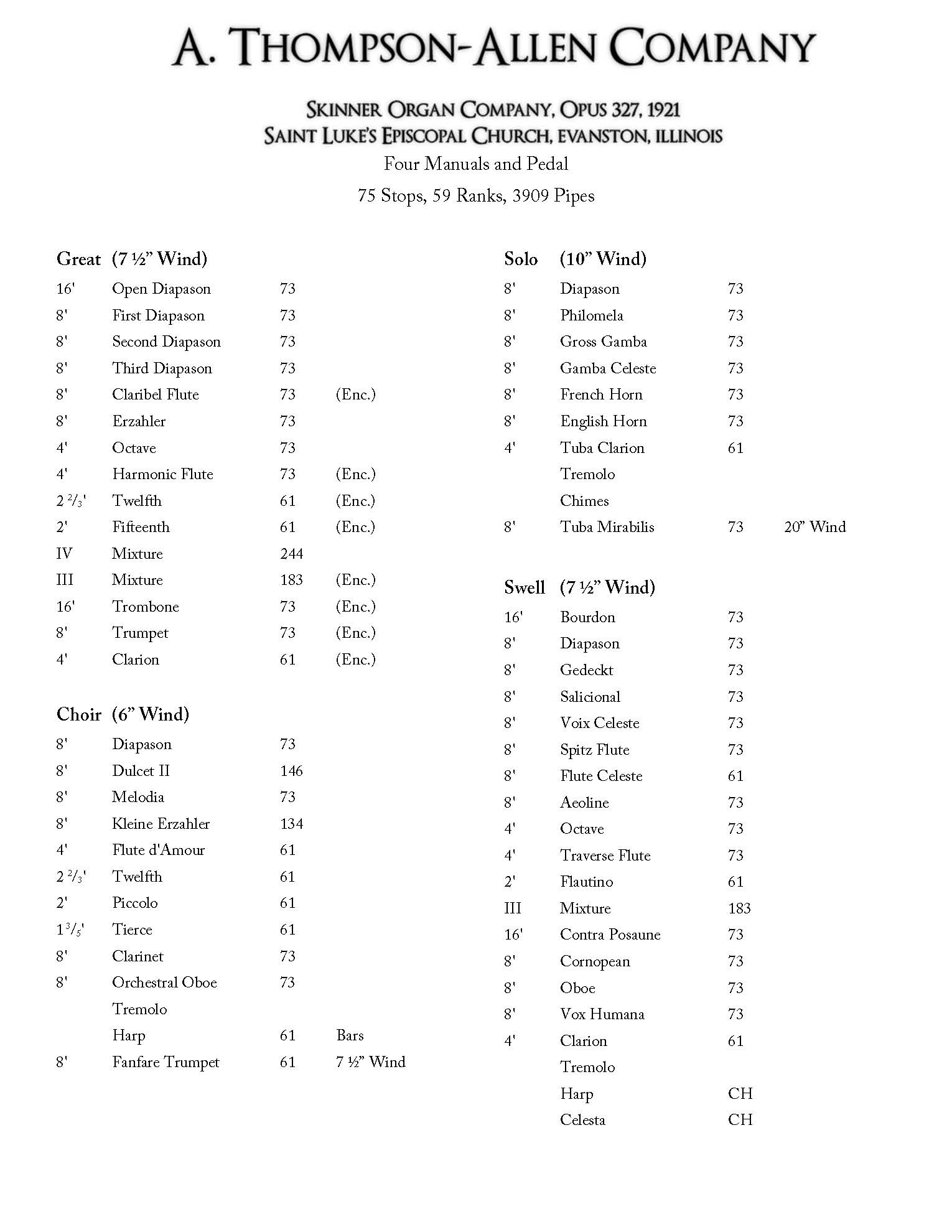

On Hinman Avenue in Evanston, Illinois, a street lined with monumental trees and gracious older homes, there is an imposing complex of limestone buildings in a restrained Gothic idiom. This is the Parish Church of St. Luke, a neighborhood institution for more than a century, and home to Skinner organ Opus 327 (1921), a four-manual organ of noble size and scale, which somehow has managed to escape many of the vicissitudes of time and the vagaries of taste. It is indeed rare to find such an important instrument from this period having so few alterations, either tonal or technological. Here is an organ at which one can sit and play, enjoying the entirety of Mr. Skinner’s justly famous creation.

St. Luke’s organ is especially significant because it pre-dates both Ernest Skinner’s 1924 return trip to England, and the advent of G. Donald Harrison’s influence in the work of the Skinner Organ Company. This instrument is a very complete realization of Mr. Skinner’s thoughts and practices for a large church organ, eloquently stated and carefully preserved.

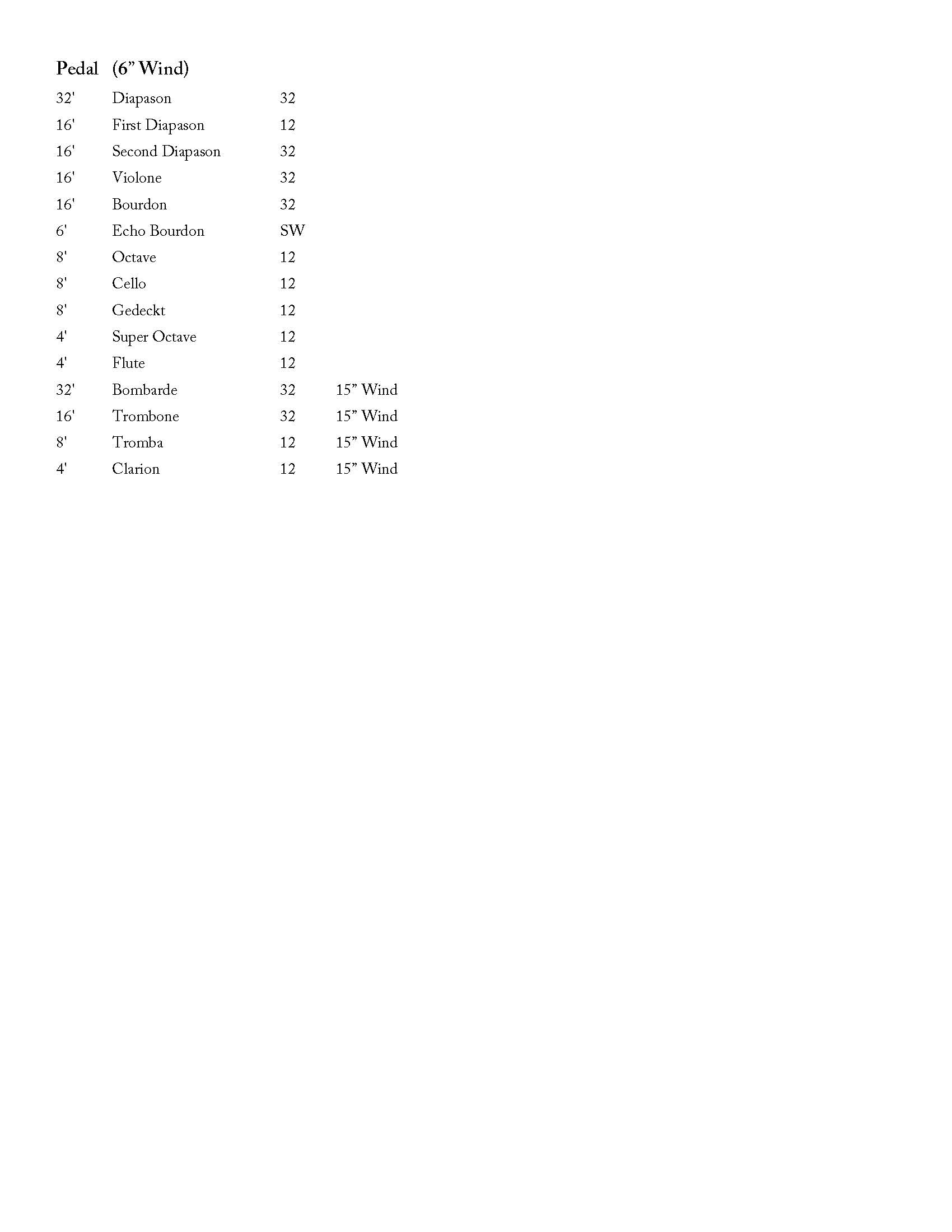

One might describe Opus 327 as an instrument the size of a three-story house, occupying the back half of a huge chamber. Fully three-quarters of the pipes are enclosed in swell boxes; these are arranged against the back wall of the chamber with the Choir Organ on the first level, the Great and Solo Organs on the second, and the Swell Organ on the third. Many of the Great and Pedal bass pipes are in the handsome organ facades; those which are not are located above the unenclosed Great windchest, at the level of the Swell chestwork. Pedal pipes are planted upon unit chests arranged in front of the wall of expression boxes. The chamber is high enough to accommodate a 32’ Diapason and 32’ Bombarde, though the latter is knuckled to keep the tops of the pipes below the arched tone openings into the chancel.

The organ had not completely escaped the notice of time, however. Wind pressures had crept higher (or lower) in some instances, original mixtures were lost, some pipework had been swapped for non-Skinner stops, and the usual additions (including a boisterous mixture on the Great and the inevitable chamade trumpet) had found their way into the stoplist. But the majority of the pipework was original, the structure and mechanism was intact (including the builder’s impressive electro-pneumatic console), and the stops which had been removed were wisely preserved in a hidden space accessible only from within the organ chamber, where they promptly were forgotten. This was a restoration begging to happen.

The work was accomplished in stages, beginning in 1993 and concluding in 1998. This schedule allowed time for fund-raising and enabled part of the organ to be available at all times for regular church duties. It is noteworthy that, for a period of many months, only the Swell division was playable. However, when such a department has nineteen ranks under expression, including two stops conveniently duplexed to the Pedal, few visitors to St. Luke’s realized they were hearing only about one-third of the instrument.

Restoration sometimes involves reconciling the present with the past. A case in point: the Chorus Mixture of the Great division. Made by Tellers and planted upon its own electro-pneumatic chest, this four-rank stop was given in the 1950s by William Harrison Barnes, local resident and renowned author of The Contemporary American Organ. The chest stood on the chamber floor, immediately behind the front pipes, presumably to give this stop as much acoustical egress as possible. The rest of the Great pipework was some twenty-five feet away, higher up and farther back in the chamber.

There were a number of problems associated with this placement. The chest was winded from the regulator for the 32’ Pedal Diapason, which produced “special effects” when the two were used together. Because the mixture and the rest of the Great Organ were so widely separated, temperature (and therefore pitch) differences were unavoidable and troublesome. And lastly there was the matter of the staggered speech from these two chests due to their separated placement; the attack was fuzzy and robbed the ensemble of clarity. The mixture came on with a bang and defiantly stood apart from the rest of the organ.

The decision had already been made to restore the missing Skinner A-9 mixture of the Great. But in recognition of the fact that the Chorus Mixture had been in the organ for so many years, and that it had come to be accepted as part of the St. Luke’s sound, it was retained in the restored organ. Its chest was moved next to the main Great chest and winded from it. The pipes were regulated to speak on the new pressure and voicing irregularities were cleaned up. While this stop now speaks with and stays in tune with the foundation stops, the reproduced A-9 mixture, though less assertive and of a different character than the Swell mixture, has been so successful that the Chorus Mixture often finds itself used only as an exclamation point to the full organ.

About the time the Chorus Mixture was added to the Great, both Skinner mixtures in the Great and Swell organs were lost. The old pipework had been rehashed to make a new, higher pitched Swell mixture; many pipes were cut down, sometimes resulting in peculiar changes in scaling, and causing the stop to fight with the rest of the Swell chorus. When the Swell was restored, a new C-15 mixture (such as is often found in Skinner Swell divisions) was furnished. Its “shower of silver” adds the right amount of brilliance to the foundation stops and the powerful blaze of the Swell chorus reeds.

The 1921 Choir stops that had been removed in favor of other used pipework languished in their cubbyhole for decades until the Choir Organ was restored. Certainly the returned Skinner Melodia and Flute d’Amour are quite beautiful, but even more dramatic is the two-rank Dulcet, a pair of 75-scale “pencil strings” tuned to produce a shimmering vibrato. This mysterious voice is perfect for spine-tingling moments during Episcopal service playing.

With respect to the console, particular attention was paid to its appearance and its unmistakable “feel.” While the casework blended perfectly with the rest of the chancel furniture and required only cleaning, the interior woodwork was in need of extensive refinishing. Original Skinner lettering was copied for the restored drawknobs; the half-dozen new knobs look at home among the originals. In the 1970s the so-called “tracker touch” was removed from the manuals, and an unsatisfactory new spring arrangement was installed at the tails of the keys, causing a lethargic, sluggish key touch. The missing Skinner parts were reproduced by two small New England machine shops specializing in precision work. Now reinstalled, the toggle-touch of the keys has returned the crisp and lively touch so characteristic of Skinner manuals.

Richard Webster, who was Organist-Choirmaster at that time and who had played this beautiful and reliable console for more than twenty-six years, asked if we might find some way to include a General Cancel piston, for such had not been specified when the console was built. The interior of the console is dense to the last cubic inch with electro-pneumatic machinery, but a way was found to install this accessory using both period and replicated Skinner parts. Probably this was the only electro-pneumatic General Cancel to be made within recent decades!

The restored organ testifies to the vision of the people of St. Luke’s and their long-standing commitment to their church and its remarkable instrument. We trust that Opus 327 will spend many more decades in service to the Parish of St. Luke, its familiar voice a vital part of worship, and its restoration a witness to wise stewardship and the enduring qualities of artistic creation.

Hello, World!