Battell Chapel at Yale University

New Haven, Connecticut

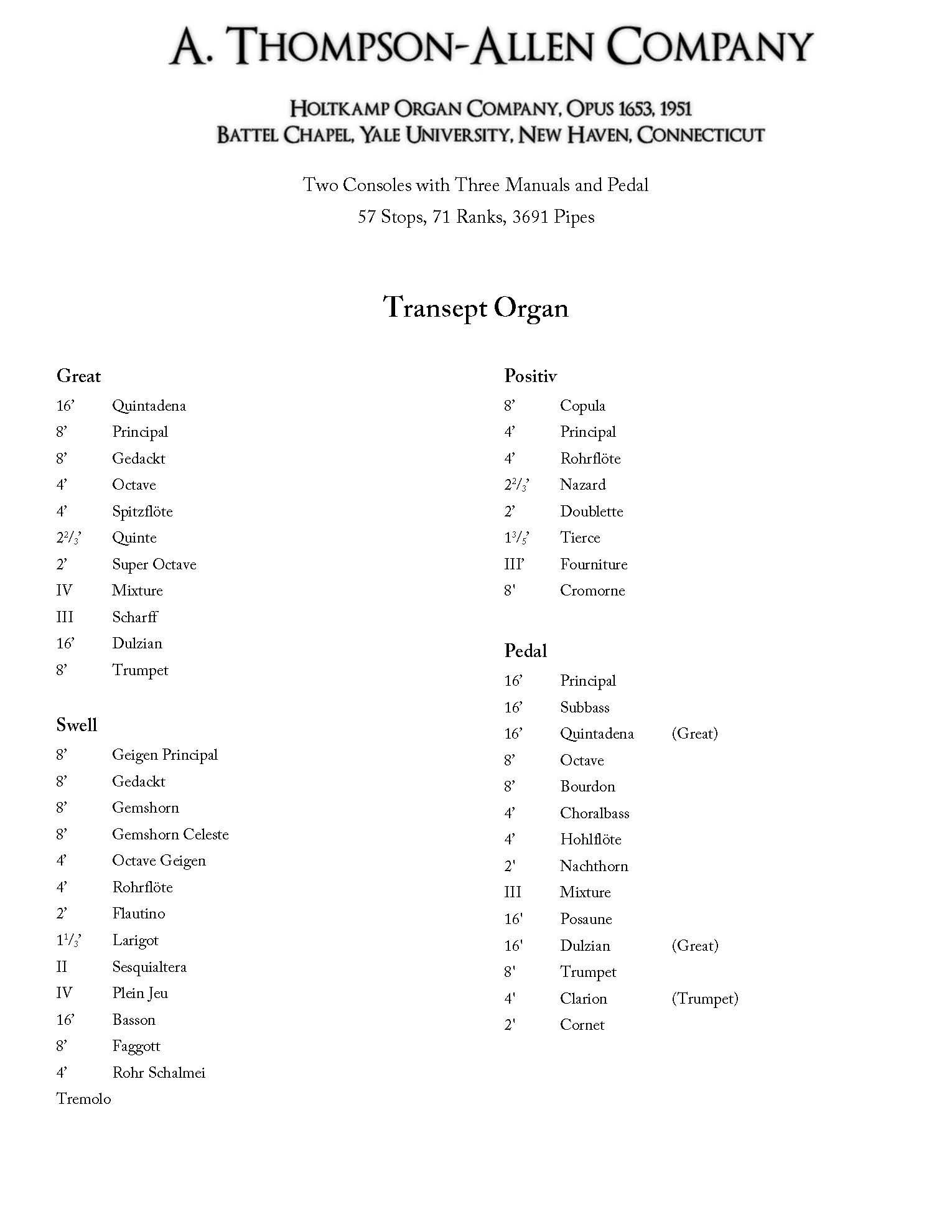

Holtkamp Organ Company, Opus 1653, 1951

Ironically, the very popularity of Walter Holtkamp's new instrument proved part of its undoing, as the organ achieved immediate acclaim and was used extensively for teaching, practice, and recitals, as well as regular Chapel services. This unavoidably heavy schedule took its toll, as did the dramatic increase in air pollution at one of New Haven's busiest intersections.

Two electric motor fires in the old blower forced toxic smoke through the mechanism and pipework of the organ, damaging the leather membranes that open the valves beneath the pipes. Battell Chapel's worn-out heating system alternately baked and steamed the instrument, but most damaging were several leaks in the century-old slate roof above the organ. The most serious of these inundated the transept pedal ranks in late 1983, silencing most of their pipes and rendering them practically useless. By then many of the organ's 3,691 pipes had become unplayable; those which continued to speak were choked with dust and even an occasional pigeon. The state of the organ was a sorry compliment to the exhaustion of the Chapel itself.

Through funding provided by the Yale Institute of Sacred Music, which was endowed by the Irwin-Sweeney-Miller Foundation, restoration of the organ was begun in January of 1984, simultaneous with the renovation of the interior of the building. A considerable portion of the organ's total weight of four and a half tons was removed from the Chapel; what remained was protected during the work of restoring the building. Metal pipes were scrubbed in hot, soapy water; wood pipes were refitted and refinished. All sixteen regulators and concussion bellows were rebuilt, and new valves were installed in all of the windchests. As the building neared completion, the interior structure of the organ was thoroughly cleaned and provided with additional worklights.

It was the intention of the restorers that the original voicing of the instrument not be altered. We hear today what Walter Holtkamp wanted us to hear; his clear ensembles, hauntingly beautiful flute stops, and the jovial buzz of the reed pipes all remain intact. His architectural treatment of the organ appears more at home than ever in the Victorian exhuberance of the Chapel. "Our Lady Battell" has regained her voice, and a certain harmony has returned to this part of Yale's life.